Battling at the Bridge

Stick Fights and Boxing Spectacles

in Renaissance Venice

About

1669 an anonymous Venetian essayist wrote a detailed history recounting

the city’s many guerra di canne or “war with sticks”.

The Chronicler of these great pugni

(or fights) wrote the battles “are not lowly things of little

importance, but of the highest consideration”. Beginning in the

late 1300s and lasting until the early 1700s, these mock battles or

battagliola, consisted of

mobs of working men with shields and in helmets pummeling each other

with wooden sticks in hours of chaotic melees. Men were routinely

injured and maimed in the fighting and inevitably some killed. The

first official note of these Venetian stick battles dates from 1369

but they apparently did not begin to occur on bridges until 1421.

The events were of such pride that the Venetian government arranged

them for honored guests. In 1493 one such event was held before the

Duke and Duchess of Ferrara. A small stick war was displayed in 1582

for Turkish diplomats and another was even held in 1585 for Japanese

ambassadors. In 1574 a bridge battle conducted

by 600 Venetian artisans was arranged for the French King Henry III.

Although, Henry later reportedly complained that the event “was

too small to be a real war and too cruel to be a game.” About

1669 an anonymous Venetian essayist wrote a detailed history recounting

the city’s many guerra di canne or “war with sticks”.

The Chronicler of these great pugni

(or fights) wrote the battles “are not lowly things of little

importance, but of the highest consideration”. Beginning in the

late 1300s and lasting until the early 1700s, these mock battles or

battagliola, consisted of

mobs of working men with shields and in helmets pummeling each other

with wooden sticks in hours of chaotic melees. Men were routinely

injured and maimed in the fighting and inevitably some killed. The

first official note of these Venetian stick battles dates from 1369

but they apparently did not begin to occur on bridges until 1421.

The events were of such pride that the Venetian government arranged

them for honored guests. In 1493 one such event was held before the

Duke and Duchess of Ferrara. A small stick war was displayed in 1582

for Turkish diplomats and another was even held in 1585 for Japanese

ambassadors. In 1574 a bridge battle conducted

by 600 Venetian artisans was arranged for the French King Henry III.

Although, Henry later reportedly complained that the event “was

too small to be a real war and too cruel to be a game.”

During the 1500s and 1600s the spectacles grew in size and

significance. Several times a year Venetian workers and tradesmen would gather on

particular Sundays or holiday afternoons to fight for possession of a bridge. These ritual

encounters were also called battagliole sui ponti

or “little battles on the bridges”. Such pre-arranged battles were known as guerre ordinate. They would take several forms from

individual duels and small-scale brawls for a few hundred or thousand onlookers to

enormous ones prepared days in advance and held for hours in front of tens of thousands of

spectators. They were waged by all types of citizens but for the most part the civili. In Medieval Pisa, we know of the

so-called giucco del mazzeascudo or men fighting

“with wooden weapons sometimes altogether, sometimes two at a time” with wooden

helmets and a padded breastplates of iron. The massive Ponte di Mezzo overlooking the Arno

River in Pisa was often used as a tournament field for similar factional battles. From at

least the tenth century in many Italian communities rival bands of youth were known to

battle in open fields using fists, stones, or wooden swords and shields. One professor of

Renaissance Italian history tells us such pretend wars between fighters wielding sticks

and rocks and protected by shields, helmets, and armour were a regular occurrence in

Italian cities during the era.

In Medieval Venice chivalric tournaments were far less common, were

conducted mostly by professional soldiers rather than Venetians, and commonly were genuine

mock battles. This allowed the Venetians the

opportunity to appraise the prowess of their own troops and reward the skillful fighters. In 1458 the Venetian commander Bartolomeo

Colleoni held a tournament battle between two squadrons of 70 men-at-arms fought with full

weapons. The contest was for possession of a small wooden castle erected outside the

Doge’s palace. This Venetian tradition of large-scale mock fighting and tournaments

ended in 1480 when horses were barred from the streets and was replaced instead by mock

naval encounters.

Originally the Venetian bridge fights were waged with sharpened

sticks or robust cane, known as canne d'India,

from local lagoons. The sticks were customarily hardened at the point

by repeated soaking it in boiling oil. Interestingly

they were employed as much for thrusting as for striking.

It is no surprise the participants typically wore an iron helmet or celada. Some

also wore iron and leather cuirasses or zacco

(mail under their shirt). A leather or wooden

shield (targa or rodella) was also a necessity. Although

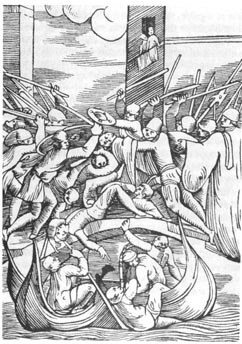

some are known to have used a cloak wrapped around the left arm. Interestingly, though the combatants are nearly

all commoners, these arms closely resemble those customarily associated with gentlemen of

the era. One woodcut from 1550 though depicts the battles with little armor, few

helms, several long staffs, and a even halberd in the background.

The battles themselves were staged and fought without

any formal or written regulations. Though no details survive of the actual

combats we can imagine that jumbled crowds of men with sharp sticks stabbing

and striking even if without intent to injure would be a quite dangerous

activity. As to the injuries,

we are told by another chronicler the participants carried on their persons

“…the scratches, sprains, teeth knocked out, dislocate jaws,

gouged eyes, and finally, smashed ribs and crippled legs”. The tension

of the events ran high and the sight of a single dagger drawn in anger

could instantly cause a hundred others to be pulled amidst the brawling

factions. Historian Robert Davis tells us “Although individual

aggression and vendetta often played a role in these violent encounters,

the real motive force behind the battagliole was the pursuit of group

and personal honor, arising from an intense factional loyalty and rivalry

that was strong enough to challenge even the absolutist powers of the

Republic's central government.”

Renaissance historians trace the Venetian factional rivalries back to

immigrants of the Rialtine Islands. Reports survive of pretend battles from as early as c.

810 between factions armed with sharp sticks or canne

d'India. In Venice the citizens formed

various factions or teams each with its own unique name and sometimes costume. The

fighting squads at the battles were typically composed of forty or fifty men from the same

neighborhood or same occupation or guild. The

two main factions formalized in 1548 where the Castellani

and the Nicolotti. One faction, the Paluani, was known for arriving at the bridges in

military order, with their squads dressed in matching uniforms. Loyalty to one’s

faction was highly prized. Faction members caught changing sides to help throw a fight

could expect violent reprisal or assassination.

Weeks before the event detailed arrangements would

be made to prepare the teams for the contest. The passion for this martial

festival on these common bridges swept up the entire city.

Fascination for the event penetrated every corner of daily life

as people of all classes were caught up. On the appointed day vendors

and food hawkers would also swarm to the bridge sites. The fans of the

events were as obsessive as any modern soccer or football fanatic. The

crowd would watch the spectacles in excitement, cheering, whistling, and

waving handkerchiefs. For one afternoon the bridge became an arrengo

or arena. To make things safer, sawdust was sprinkled on the bridge stones

to prevent slipping, straw padding was placed around the bridge abutments

in case of falls, and the water below was cleared of rubbish or debris.

Once the battle began the water below the bridge would be jam packed with

barges and boats and gondolas until no water was visible.

The crowd was in effect the ultimate arbiter and determined

by applause or condemning hisses which fighters and which side had acted

honorably or cowardly. The battagliole

were also celebrations of personal honor as men fighting in pairs or in

large mobs on a public stage thought to gain name and recognition among

their peers and spectators. Factional

leaders called padrini were chosen from the champions of each

side. They were charged with not only leading and organizing the factions,

but partitioning them safely and equally in the piazza before the fight

as well as planning safe routes for each side to take to the bridge site

beforehand. Each contingent of 50 factionaries from a neighborhood was

itself headed by a capo or “boss”,

responsible for recruitment and discipline.

The crowd too could

become riotous. Pumped up by wine they sometimes might begin throwing

roof tiles off of nearby balconies (stripping them almost entirely bare

in the process!). More than one event was halted because of the trouble

this caused. As well, gentlemen viewing from opposing “box seats”

might loudly exchange words and insults which could lead to swords being

drawn then and there or an arranged duel occurring afterwards. The militia

often had to break up battles that got out of hand. Local

aristocrats would step into the factions and attempt to lower passions.

Often their intervention held more respect than either that of the municipal

authorities or the factional leaders themselves.

The Venetians were always highly sensitive about factional

honor and many were ready to defend against perceived insults from other factions using

the weapons that every artisan routinely carried about the city: the handy stiletto (stillo)

or the broad pistolese (also known as the lengua de vaca, or cow's tongue)

as well as spiked boat poles (spontoni) used in the city canals. Some also stuffed

their work aprons (traverse) with handfuls of iron balls or stones (cogoli),

to be thrown with lethal effect from a safe distance. Davis adds “Arguments between

even two or three enthusiasts over the merits of their respective faction could thus

easily result in bloodshed and massive brawls, the more so since—as one English

observer noted—Venetian commoners were far more likely to join in a fight than to

assist in breaking it up.”

As early as 1505 the Venetian Council of Ten in the

name of public order began to punish those who assembled for the bridge

wars. Supplies of sticks had to be secured and hidden between events.

But like laws against dueling, their efforts largely went ignored and

were often repeated. Gangs of armed youths would get caught up in the

excitement and frequently rumble with their rivals or the police. Many

of those involved in neighborhood contingents were street toughs or raffines. We know for example of one, Tonin,

a Caporione tailor from San Luca who

in the 1630s was described as “an assassin” who “lives

by arms… gathering about him at his expense a large gang of miscreants

[malviventi] with whom he has

assaulted and killed many”.

Due to the state’s opposition to the disorder

caused by these popular pastimes, by 1600 the bridge fights in Venice

ceased to use sticks and became unarmed brawls called guerre

di pugni or “war of the fists”. As with the stick wars,

these bare-handed sporting brawls could attract thousands of fighters

and tens of thousands of spectators. The new mode of combat apparently

caused great curiosity and wonder. A possibly apocryphal explanation for

the transition from sticks to fists supposedly occurred in 1585 when one

faction ran out of sticks but continued to fight on unarmed and the other

faction matched them. Ironically, this was not out of honor, but because

they could no longer “fence” with their opponents and were instead

being punched in the face and chest. Because the injuries from fist blows

were readily seen to be more significant, the other side cast away its

weapons. One historian adds: “At the same time, there are signs

that the nature of the battles themselves began to change under the 'civilizing'

influences of police and patricians. Whereas earlier in the century it

had been customary to stage a few (but rarely more than half a dozen)

individual boxing matches (known as mostre, or "showings")

as a sort of warm up before beginning the actual mob attack on the bridge

(the frotta) that was the main event, by the 1660s, there are indications

of a shift of emphasis from group brawling to single combat.”

The Venetians became well-known for their pugilistic

skills by the late 1600s. The Slavic soldiers, Dalmatia or Schiavoni, were regularly thrashed and thrown into the water by the

jabbing skill of the Venetian boxers. One source says that although the

Slavs were accustomed to “coming to the clinch with sharp steel,”

in the unarmed bouts they swung their arms about ineffectively as if they

still had blades. This is

an interesting anecdote about the application of military cut-and-thrust

skills compared to the calculated jab of boxing–which interestingly

resembles the classic foyning thrust of late Renaissance fencing.

Eventually, one-on-one boxing matches called mostre began to take place before the

general bridge assaults. The term mostra

means a display or exhibition; the actual fighting of the boxing match

was called a cimento or steccado.

These “duels” became more and more popular. The pugni or “boxers” would wear

leather or even “paper” chest armour and prided themselves on

their fine dress. Later they began to go bare-chested, wrapping their

shirts around their waists to protect their kidneys from punches. The

fighters would typically wear only one padded glove or guanti of soft or hardened leather

on their right hand, but by the end of the 1600s wore two gloves. Sometimes

their gloves were even secretly sewn with lute strings so as to rapidly

bloody an opponent’s face. The object of the mostre

was not to score a knock out or to deliver powerful punches, but to bloody

the opponent by a hit to the nose, lip, or face.

The boxing fights or cimenti,

were divided into rounds during which the combatants returned to their

respective corners. The rounds were known as assalti (assaults) or salti (jumps or dances). The fighter or duelista fought for his personal honor and reputation. Display was

important and each fighter was expected to “show himself well”.

As one historian describes it, by their performance and the abuse they

underwent, the fighters in effect laid claim to the public’s adoration

and respect (much like the later 19th century German university

student’s Mensuren ritual duel). In these “boxing”

matches the crowds evidently were most pleased by contestants who stood

their ground and took blows to their face unflinchingly, striking out

cleanly without too much dancing or fencing around (“troppo gioco

nella scherma”). Defensive skills were less admired than displays

of courage.

We are also told how sometimes these events “would

be upset by the fighters themselves, who might well explode in a factional

frenzy under the numbing stimulus of ample draughts of free wine and the

deafening cries and whistles of as many as 30,000 onlookers, ending up

turning on each other with drawn daggers and machetes. Some of the more

aggressive spectators might also decide to join in the action, punching

those nearby, brandishing weapons, or lobbing paving stones into the thick

of the scrum. In either case, the result was predictable and often

deadly, as all boundaries between the factions, the fighters and the onlookers

dissolved into a stone-throwing, knife-wielding melee, sending men and

women from both factions scrambling panic-stricken away from the deadly

battle field.”

The “cult” of the pugni

was about the value of the individual and his prowess, aggressiveness,

and proper conduct. These champions were treated as star athletes, being

welcomed by wealthy patrons and nobles as heroes as important as any victorious

soldier. Surprisingly, foreign mulattos were even occasionally brought

in as ringers by wealthy faction supporters and several became popular

champions (shades of today’s heavyweight prize fighters 300 years

later!). Like star athletes, the best champions would gain fame and fortune

all over the city. Their image would be lionized and depicted in paintings,

cartoons, and effigies.

It is worth noting that in the mostre, “Grappling and wrestling were condemned less as unfair

fighting than as a coward’s way of avoiding his rival’s punches;

when a duelist would not allow himself to be turned into a beast.”

Fighters instead relied on solid exciting blows that factional honor required.

In some cases apparently combatants even agreed before hand to pull punches.

Despite all the ferocity and display, the fights were fairly benign affairs

and ended with an embrace and fraternal kiss. A fighter who had been unfairly

dishonored by a fellow pugni might also seek a vendetta with

his compadre and the support of the sect

of his faction. He might be backed in his quest by wealthy merchants and

nobles so that steel would later settle the matter through blood.

By the late 1600s

weapons and armour were dropped from the bridge fights entirely. The Chronicler

of the events suggests there was only room for one form of fighting, and

once the stick fighting fell out of popular favor it could not exist alongside

the very different fist fighting.

The story argues boxing “won out” over stick fighting. As historian of the bridge wars Robert

Davis suggests, “That an essentially naked man should triumph over

a heavily armored adversary was itself–in an age dominated by professional

soldiers, hierarchical armies, and not a few remnants of chivalric ideas–a

seeming paradox charged with republican and egalitarian.” He adds,

“The boxer’s victory was one of pragmatism… the results

of an intrinsically plebeian decision as to what worked best at the bridges.”

We can imagine wooden weapons being easy enough in a crowded melee

to use in banging on another’s shield, helmet or stick, but unarmed

fighting, even if just straight jabs, required closing to shorter range

and direct contact flesh on flesh.

The change from sticks to fists may also reflect the changing nature

of war in the period, when individuals' skill in traditional arms was

becoming less and less important than firepower and close order drill

in formation. By the late 1600s

weapons and armour were dropped from the bridge fights entirely. The Chronicler

of the events suggests there was only room for one form of fighting, and

once the stick fighting fell out of popular favor it could not exist alongside

the very different fist fighting.

The story argues boxing “won out” over stick fighting. As historian of the bridge wars Robert

Davis suggests, “That an essentially naked man should triumph over

a heavily armored adversary was itself–in an age dominated by professional

soldiers, hierarchical armies, and not a few remnants of chivalric ideas–a

seeming paradox charged with republican and egalitarian.” He adds,

“The boxer’s victory was one of pragmatism… the results

of an intrinsically plebeian decision as to what worked best at the bridges.”

We can imagine wooden weapons being easy enough in a crowded melee

to use in banging on another’s shield, helmet or stick, but unarmed

fighting, even if just straight jabs, required closing to shorter range

and direct contact flesh on flesh.

The change from sticks to fists may also reflect the changing nature

of war in the period, when individuals' skill in traditional arms was

becoming less and less important than firepower and close order drill

in formation.

While the bridge battles consisted mostly of working

class artisans and laborers, the nobility did participate. Until at least

the 1580s aristocrats were involved heavily in the battagliole

and their chronicler tells us: “In these old-styles the more fiery

and pugnacious nobles were accustomed to go to the bridges… armed

with light helmets, heavy gloves, and cutlasses, to serve as auttorevoli padrini.” The change from armed to unarmed surely

finished off the involvement of aristocrats in the actual combat. The

late 1600s Venetian guidebook of Alexandre Saint Disdier described that

the nobility delighted in seeing “these fights and battles, while

for the common people it is an affair of reputation and of importance.” Primarily, the nobility as spectators

would watch from rented balconies or moored boats, but their role as fans

and supporters did play an essential part in the promotion and success

of the battles.

The crowds of patricians would waive their handkerchiefs

to show approval and enthusiasm of their side. Hundreds

might waive in unison as a signal to the opposing noble spectators to

challenge them to send forth a duelist or even to admit defeat. When

shaken rapidly, handkerchiefs could be a sign of contempt that the opposing

fights were weak or cowardly. By the mid-1600s nobles had almost entirely

ceased participating and only took active roles as leaders before the

clash. As spectators however, gambling on the battles was considerable

(just as with modern day sporting events). To organize these events and pull

them off required considerable negotiation on behalf of the artisans and

workers, the faction leaders, the wealthy merchants who backed them, and

the nobility who supported (and gambled on) them as well as government

officials concerned with public safety and order. Interestingly, as with

modern sport teams, the neighborhood merchants would endorse and support

their factions, including handling their uniforms.

Similar

events to the Ventian battles were held in Florence on special occasions

in the late 1500s and early 1600s, sometimes between guilds of dyers and

weavers. The combat might last 30 minutes or more. Such fights were also very

common in Pisa, where they occurred on the city square and were used

as a form of martial exercise as well as sport (such events continue into

the present day). By the 1500s they began to be played on small bridges.

A wooden weapon called a mazza-scudo and a small shield were originally

used. Typically metal helms with padding of cotton or horsehair were worn,

as was some degree of iron body armor. Other men wore less armor and participated

as light fighters. A special tool called a targone, part shield,

part weapon was also employed. Attacks were allowed with the blow and

the point to the adversary’s head, arms, and chest.

The guerra di

canne represent an interesting part of martial sports in European

history, and shed insight on a rarely considered aspect of Western martial

culture. While there are similar accounts of mock battle sporting events

in Italian history, because of their distinct and almost entire

concentration on bridges, the Venetian events are unique. As a writer at the time expressed:

“The purpose of our combat and contests is not to kill each other

or tear each other apart, but only, in the presence of the city, to win

and to take possession of the bridge, with competition and with the usual

audacity.”

To read more about this, see “The Police and the Pugni: Sport and Social

Control in Early-Modern Venice”.

Robert Davis. Stanford Humanities Review, 6.2, 1998, The War of the Fists–

Popular Culture and Public Violence in Late Renaissance Venice, Oxford University Press 1994, and Mercenaries and

Their Masters - Warfare in Renaissance Italy. Rowman and Littlefield,

1974.

Back to the Essays Page |