Historical

Fencing Studies Historical

Fencing Studies

– the British Legacy

By

John Clements

At

present, for a dedicated few, the pursuit of Renaissance martial

arts is far more than just a passing interest or curiosity or another

in a long series of martial arts fad. It is a sincere way of studying

historical skills while connecting to the cultural roots of their

own heritage. Yet, interestingly this

recent effort to follow "old swordplay" is not the first.

Such an effort actually was underway over 100 years ago and

in, of all places, Britain. Several Victorian

military men, namely Captain Alfred Hutton, Egerton Castle, Captain

Carl Thimm, Colonel Cyril Matthey, Sir Frederick Pollock, and Captain

Sir Richard Burton, were fencers interested in the history and practice

of antique forms of fence. Their legacy

is with us in the current resurgence of historical fencing interest

now underway.

In

the preface to his famous 1896 complete bibliography of fencing and

dueling, British researcher Carl Thimm stated "all forms of fencing"

were seeing at the time a "revival" after a "long period of abeyance".

Thimm referred to the subject of fencing history as one "hitherto

fraught with much 'legend and phantasy'" –a problem it

has by no means entirely escaped today. In

the preface to his famous 1896 complete bibliography of fencing and

dueling, British researcher Carl Thimm stated "all forms of fencing"

were seeing at the time a "revival" after a "long period of abeyance".

Thimm referred to the subject of fencing history as one "hitherto

fraught with much 'legend and phantasy'" –a problem it

has by no means entirely escaped today.

Thimm's

own fencing bibliography presented a list divided by country and date

of everything he could find on fencing and duelling ever published.

It proved so popular that, in 1891, it was translated into

French and German. Enlarged and revised in an 1896 edition, it was

the most complete compilation on the subject at the time, even superceding

contemporaneous Italian and French attempts.

Though Thimm often listed titles he had never seen or read

and duplicated or incorrectly listed many entries, even today his

work serves as a primary resource. Thimm, who in his

writings distinguished several times between "modern and historic

sword-play", stated "Investigation of the doctrines of ancient

masters of fence and bibliographic compilation of fencing works were

things naturally bound to go hand in hand". This is even truer at

the present time when such efforts have reached a greater intensity

than ever before. Thimm

claimed the modern interest in historical fencing books at the time

was instigated by the publication of the French fencing bibliographer

M. Arsene Vigeant's 1882, La Bibliographie de l'Escrime Ancienne

et Moderne, which increased the price of such texts thereby causing

them to be highly sought after.

| Thimm's fellow British fencer and sword scholar,

Captain Alfred Hutton, was one of several who pursued his own

study of the styles chronicled in Renaissance fighting manuals.

In the preface to his 1892, Old Swordplay, Captain

Hutton declared, "There are those who affect to ridicule the

study of obsolete weapons, alleging that it is of no practical

use; everything, however, is useful to the Art of Fence which

tends to create an interest in it, and certain it is that such

contests as 'Rapier and Dagger', 'Two hand Sword',

or 'Broadsword and Handbuckler,' are a very great embellishment

to the somewhat monotonous proceedings of the ordinary 'assault

of arms'" (i.e., the classical fencing sport).

Hutton also tells us that, "the fence of the case of rapiers,

as of all the other Elizabethan weapons, is much in vogue

at the present time at the Baritsu club, now the headquarters

of ancient swordplay in this country."

The Baritsu club ironically was itself teaching an

eclectic English form of self-defense created by combining

boxing, wrestling, and Savate with elements from Japanese

jujitsu and had among its members Arthur Conan Doyle.

The group of Hutton and his associates was quite active in

studying and practicing historical fencing.

Sir Frederick Pollock had written numerous articles

on the subject and in 1890 given a lecture at Oxford on "The

Forms and History of the Sword". In

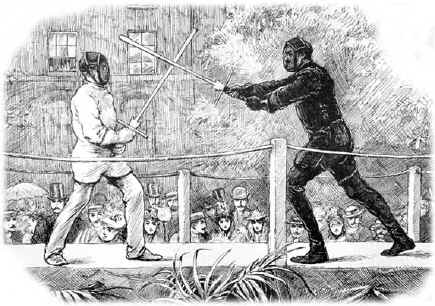

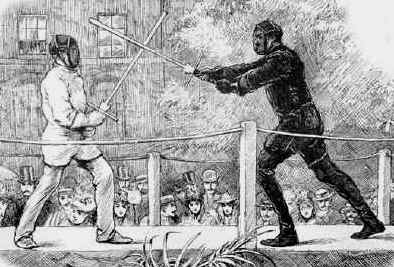

an 1891 exhibition of historical fencing at the Lyceum theater

in London, Alfred Hutton and Egerton Castle along with Sir

Frederick even included a demonstration of the so-called "mysterious

circle" in their presentation. Thimm described the event as

"an actual, living, panoramic display of the evolution of

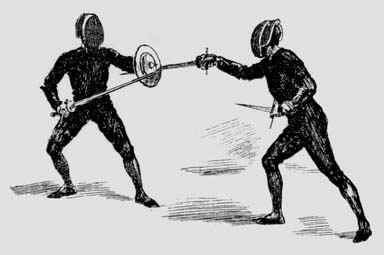

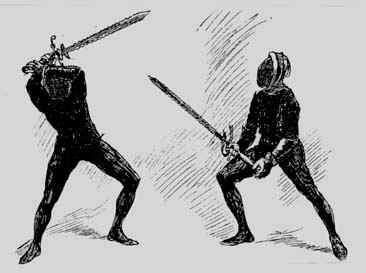

the fencing art." Illustrations

of the event from a London newspaper of the time depicted

Hutton and Castle fencing with the two-handed sword, sword

and buckler, rapier and cloak, rapier and dagger, single-rapier,

and small sword. Another such display was given in 1895 by

Hutton's own fencing students from the London Rifle Brigade.

|

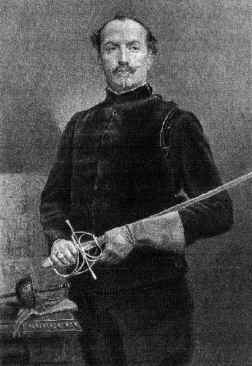

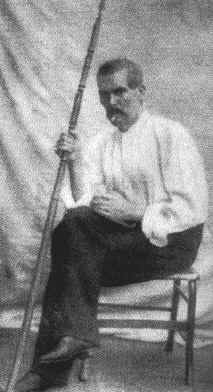

Hutton in his

Prime

|

|

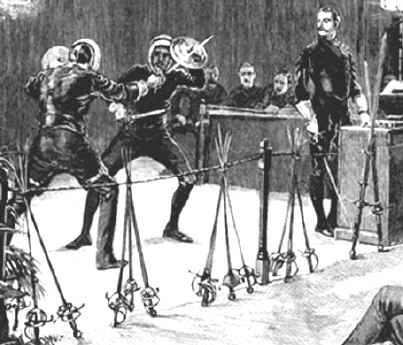

Hutton overseeing

a 1891 public exhibition

|

In 1892, the Oxford

University Fencing Club presented a demonstration and lecture by club

president Sir Frederick, "explaining the transition of swordsmanship

from the old English Sword and Buckler fight to Rapier and Dagger"

accompanied by "prominent fencing historians" Egerton Castle and Captain

Alfred Hutton re-creating an "Elizabethan prize at verie many weapons".

In 1893, Hutton gave a presentation of "Swordsmanship, Medieval

and Modern" at the Manchester Gentlemen's Concert Hall.

In 1897, Hutton wrote an article for The Indian Fencing Review

on "Sword Fighting and Sword Play", directed toward the infantry officer

and which among other things observed differences between military

fencing needs and classroom teaching by invoking material from Silver's

newly discovered Brief Instructions. Foreshadowing much of

today's historical fencing presentations on the teachings of the old

masters, in 1897 Hutton (at the age of 57) also gave a related display

of George Silver's "grips" at the Whitton Park Club. While elaborate

"assaults of arms", or displays of civilian and military fencing,

were not uncommon in Victorian Britain, the events of Hutton and Castle

were something else entirely.

| Thimm

also recounted a "magnificent display of historical fencing

which took place in Brussels in the spring of 1894".

He tells us the charity event, called Le Cycle de l'Epée,

"derived its chief element of success from the presence and

active help of Captain A. Hutton and several English officers

of Volunteers who went over to lend the weight of their special

and remarkable dexterity". That

same year, Hutton recounted a historical fencing display (perhaps

the very same one) held in Belgium by the fencers of the London

Rifle Brigade.

Hutton was very active in his presentations.

He wrote an article in 1867 called, The Cavalry Swordsman,

one in 1887 called, Swordsmanship,

for the use of Soldiers, and delivered a lecture on

"Our Swordsmanship" at the Royal United Service Institution,

Whitehall, in 1893. In 1895 he gave another, "Notes on Ancient

Fence" at the Albany Club.

Hutton described

how when the participants first "began to interest themselves

in this ancient work they were mere boys in their teens,

but they attained to such proficiency in the handling of

two-hand swords, rapiers, and the like, that they were able

to visit various schools and to enthuse those by exhibitions

of fighting with all kinds of weapons".

This is much the same approach today.

Neither then nor now could they rely on traditional

fencing schools for instruction.

|

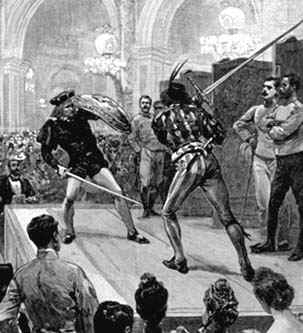

A rare demonstration

of great swords at a Fete du

Arms

in Paris, c1900.

|

|

To put the research

and efforts of these men in context, it is important to establish

upfront that the old methods of Medieval and Renaissance fencing skills

did not survive past the 1600s. The changes in warfare and in society

over the centuries precluded these skills from being used or passed

on. The advent of the French system of

small-sword duelling in the 17th century also eclipsed

older obsolete methods of armed combat. While rival schools of French

and Italian fencing styles were dominant in the 19th century,

and some elements of older Spanish traditions were still active, nothing

survived like the methods from the 1400s and 1500s.

The newer style of small-sword play, suited specifically for

single combat duels of single sword, adapted rapier fencing but did

not much carry it on. By the late 19th

century, the older classical styles were rapidly fading and the sporting

form of fencing which had developed was slowly but surely dominating.

The rediscovery of essentially lost methods of swordplay

was therefore a new field of inquiry. Speaking

in 1891 on the "story of swordsmanship", Captain Hutton's colleague

and fellow student of the sword, Egerton Castle explained how his

recent displays of "historical" fencing methods were "an attempt to

promote a revival of an art which may be said to be almost dead."

Hutton

from Old Swordplay, posing with a rapier Hutton

from Old Swordplay, posing with a rapier |

Born in 1839, Alfred Hutton

served with the army cavalry in India and learned several

Oriental languages. He was a member of the King's Dragoon

Guards and founded a School of Arms in all three of his

regiments wherein he gave "many exhibitions of ancient and

modern fencing". Hutton had written numerous articles on

historical fencing in the 1890s. He was President of the

Amateur Fencing Association in England and considered "quite

an authority on the history of the sword." His first work,

Old Swordplay– The Systems of Fence in Vogue

During the XVIth, XVIIth, and XVIIIth Centuries, with

lessons arranged from the works of ancient masters,

Hutton presented material for practicing the use of the

sabre and stick as well as historical lessons based primarily

on a reading of Achille Marozzo's 1536, Opera Nova.

Much like any martial arts

writer, Hutton attempted to provide simple lessons for students

without their having to go through the labor of searching,

as he put it, "old books in various languages some of which

are very difficult to procure and much more so to understand."

In 1889, he produced, Cold Steele: A Practical

Treatise on the Sabre, covering sabre, baton, epee,

and dagger, based on 18th century English backsword

combined with modern Italian duelling sabre. In addition

to a method of military saber use, the book offered a variety

of exercise material from 16th century texts, including

Marozzo and also included self-defense material on the modern

constable's truncheon and the short sword-bayonet. In 1901,

Hutton published his delightful, The Sword and

the Centuries - Or Old Sword Days and Old Sword

Ways, a brief survey of Medieval and Renaissance fencing

attempting to cover five centuries of sword duels and the

changes in fencing that took place.

Hutton was not only an accomplished fencer and military

man with a realistic appreciation for swordplay, he was

a keen student of history with a sincere interest in reviving

Renaissance martial arts. His

colleague Colonel Matthey said in England Hutton's name

had long been a "household word" among "lovers of the art

of fence". He died in 1910 at

the age of 71. (The Sword and the Centuries

is still available in modern reprint and Old

Swordplay is to be republished in 2002.)

His collection of fencing books is now in the Victorian

and Albert Museum in London while some of his antique swords,

including blunt practice rapiers, are now in the Royal Armoury

in Leeds.

|

In

many ways, the assumptions and views of a gentleman of his time accordingly

colored Hutton's views and understanding of earlier fencing as well

as those of his colleagues. But they were also combined with a military

man's practical skill at arms. The same

can be said for Castle who in 1885 with his famous and influential,

Schools and Masters of Fence: From the Middle Ages to

the Eighteenth Century, did so much to codify forgotten fencing

culture. This colossal tome became the

standard reference work on the subject throughout the 20th century.

Castle dedicated his work in part to Hutton and also the Baron de

Cosson "in recollection of many pleasant hours spent…among old

books and old arms". First

published in 1885, then revised in a 1892 second edition, a third

updated edition was not published until 1969 –and then a mere

1000 copies. More than thirty years later, a modern reprint

is finally underway. In

many ways, the assumptions and views of a gentleman of his time accordingly

colored Hutton's views and understanding of earlier fencing as well

as those of his colleagues. But they were also combined with a military

man's practical skill at arms. The same

can be said for Castle who in 1885 with his famous and influential,

Schools and Masters of Fence: From the Middle Ages to

the Eighteenth Century, did so much to codify forgotten fencing

culture. This colossal tome became the

standard reference work on the subject throughout the 20th century.

Castle dedicated his work in part to Hutton and also the Baron de

Cosson "in recollection of many pleasant hours spent…among old

books and old arms". First

published in 1885, then revised in a 1892 second edition, a third

updated edition was not published until 1969 –and then a mere

1000 copies. More than thirty years later, a modern reprint

is finally underway.

Castle's

Schools and Masters of Fence

presented an overview of fencing styles and methods discerned from

readings of major 16th and 17th century manuals. Though somewhat uncommon

to locate a copy today, Castle's influential work is invaluable for

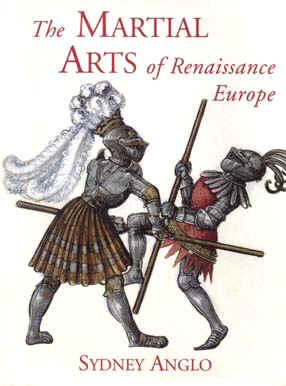

students of historical fencing. Until the recent publication of Dr.

Sydney Anglo's new voluminous and matchless labor (Renaissance

Martial Arts), Castle's remained unsurpassed for more than 100

years. Castle's book brought considerable

awareness of Renaissance fencing to new generations of fencers who

typically were, frankly, ignorant of their own heritage.

That his work presented substantial material that the major

European fencing schools in his day were seemingly no longer aware

(or at least appreciative) of is justified by the appreciation shown

to him at the time. His was elected a

member of the French Academie of Arms in Paris and given the honorary

title of master di scherma "in recognition of the service rendered

to artistic swordsmanship." Castle's

Schools and Masters of Fence

presented an overview of fencing styles and methods discerned from

readings of major 16th and 17th century manuals. Though somewhat uncommon

to locate a copy today, Castle's influential work is invaluable for

students of historical fencing. Until the recent publication of Dr.

Sydney Anglo's new voluminous and matchless labor (Renaissance

Martial Arts), Castle's remained unsurpassed for more than 100

years. Castle's book brought considerable

awareness of Renaissance fencing to new generations of fencers who

typically were, frankly, ignorant of their own heritage.

That his work presented substantial material that the major

European fencing schools in his day were seemingly no longer aware

(or at least appreciative) of is justified by the appreciation shown

to him at the time. His was elected a

member of the French Academie of Arms in Paris and given the honorary

title of master di scherma "in recognition of the service rendered

to artistic swordsmanship."

Egerton

Castle's early youth was spent on the Continent studying in Paris.

He came to England at the age of sixteen to study at Glasgow University

followed by time spent at King's College (London), Trinity (Cambridge),

the Inner Temple, Sandhurst, and Chatham. "He became, in turns, student

of History, Law, and Natural Science; and lastly soldier." Interestingly,

he was a free-lance journalist, eventually joining the staff of the

old Saturday Review. He was vice-president of the Navy

League, of which he was one of the earliest members. He was even a

successful novelist, writing several romance fictions with his wife.

A contemporary account of Castle described him thusly: "Mr. Egerton

Castle hides a kindly nature beneath his bellicose expression. His

figure is one emphatic protest against the sombre utilitarianism of

twentieth century clothes. A neat rapier would be something; but even

that comfort is denied to him in modern walking dress. His method

of fence is as graceful and romantic as the construction of his novels.

He says that his pen is mightier than his sword; as a matter of perfection,

there is little to choose between them. In Mr. Egerton Castle, indeed,

the play of the sword and the work of the pen have a definite relation." Egerton

Castle's early youth was spent on the Continent studying in Paris.

He came to England at the age of sixteen to study at Glasgow University

followed by time spent at King's College (London), Trinity (Cambridge),

the Inner Temple, Sandhurst, and Chatham. "He became, in turns, student

of History, Law, and Natural Science; and lastly soldier." Interestingly,

he was a free-lance journalist, eventually joining the staff of the

old Saturday Review. He was vice-president of the Navy

League, of which he was one of the earliest members. He was even a

successful novelist, writing several romance fictions with his wife.

A contemporary account of Castle described him thusly: "Mr. Egerton

Castle hides a kindly nature beneath his bellicose expression. His

figure is one emphatic protest against the sombre utilitarianism of

twentieth century clothes. A neat rapier would be something; but even

that comfort is denied to him in modern walking dress. His method

of fence is as graceful and romantic as the construction of his novels.

He says that his pen is mightier than his sword; as a matter of perfection,

there is little to choose between them. In Mr. Egerton Castle, indeed,

the play of the sword and the work of the pen have a definite relation."

|

|

Hutton

and Castle at rapiers (from

a newspaper article of the time)

|

Monumental as it was in exploring the "all

but forgotten origins of modern fencing", Schooles and Masters

was still flawed in many areas.

Castle was among the first to document the perceived idea of

Western fencing being a "process of progressive transformation"

or linear "evolution". This pervasive view of "old

swordplay" survived and influenced nearly all masters, historians

and writers of fencing from the early 20th century on through

to the present. Much of this can be traced back to

Castle's work.

Though he endeavored in his work to understand

the reality of earlier swordplay, as a fencing scholar more than a

martial artist, Castle lacked an appropriate conception of the effectiveness

of Medieval weapons or the nature of fighting either in armor or in

group combat. Therefore,

in hindsight, some constructive criticism of Castle is justified after

all these years. Castle's biggest weakness was that he was unaware of any fencing

texts earlier than the 1530s.

He missed the entire range of 15th century texts

and masters. He revealed a frequent Victorian bias in favor of the

traditional fencing conceptions of his day (i.e., foil/epee/saber)

with statements such as: "There are many reasons to believe that

the art of fencing made very little progress in the right direction

until about the middle of the sixteenth century." This "progress",

of course being defined by the standards of his time as that which lead directly to "proper"

foyning fence of single duel. He also

made statements about the "clumsy old fashioned sword" and

the "relatively barbarous sword and buckler".

Ironically, Castle himself observed, "Writers on

the Art of Fence have hardly ever found it worth while inquiring on

the origins of the methods they expounded."

|

Hutton & Castle at Sword

& Buckler, 1891,

and Two-handed Swords below

|

|

It's remarkable how good Castle & Hutton's form appears

in the artist's images. Both of them seem to have a good

idea of the proper stances and postures.

|

Writing in 1911 Castle still mistakenly believed

"the first cultivation of refined cunning in fence dates from

that period, which corresponds chronologically with the general disuse

of armour." Castle even became aware of the work by the great

15th century Italian martial arts master, Fiore dei Liberi, and (though

he offered no source) stated he "was known to be flourishing

as a master of fence as early as 1383." Castle continued to maintain

that it was in "the latter half of the 16th century, that swordsmanship

pure and simple may be said to find its origin; for then a great change

is perceptible in the nature and tendency of fence books: they dissociate

themselves from indecorous wrestling tricks, and approximate more

and more to the consideration of what we understand by swordsmanship."

His last statement of what "we" understand is most telling.

He continued to miss the whole essence of earlier forms of fencing

as being martial arts, not mere single sword play, when writing for

instance: "The older works expounded the art of fighting generally;

taught the reader a number of valuable, if not 'gentlemanlike,' dodges

for overcoming an adversary at all manner of weapons." Indeed,

they did. That was their entire objective.

Despite his many observations and insights into

Renaissance fencing, more than once Castle contradicted himself terribly

in his opinions. For, while he recognized that the

fencing of his day had changed considerably in both form and character

from styles of earlier ages, and that earlier methods were quite formidable,

he was unable to see deeper. Even with his and Hutton's remarkable

exploration of the subject, Castle's views on earlier swords

and fighting skills occasionally tended to reflect a multitude of

simplistic, inaccurate, and often unfounded views. For example, he declared: "The rough untutored fighting

of the Middle Ages represented faithfully the reign of brute force…The

stoutest arm and the weightiest sword won the day…Those were

the days of crushing blows with mace or glaive, when a knight's superiority

in action depended on his power of wearing heavier armour and dealing

heavier blows then his neighbor, when strength was lauded more than

skill". In a classic

example of period bias, Castle also maintained, "It can be safely

assured that the theory of fencing has reached all but absolute perfection

in our days, when the art has become practically useless."

Unwittingly, Castle also claimed: "Instead of 'down right

blowes,' Medieval fencers devised a multitude of wily attacks, and, in the absence of

any very definite mode of self-defence (which had yet to be invented), everyone indulged

in as much as fantasy in his sword-play as his individual energy allowed him to carry

out." He further described the Renaissance as "the days when something more than

brute strength became a requisite in personal combat." He even suggested a knight

"otherwise learned little of what would avail him were he deprived of his protecting

amour" and astoundingly further held that, "Indeed the chivalrous science never

had anything but a retarding effect on the science of fence."

However, Castle did display an appreciation for

the brutal practicality of earlier methods as distinguished from classical

academic fencing. Writing in 1891, for instance, he

cited the importance of knowing, not only the proper manner of "coming

to point" in "matters of honourable difficulty", but

also of the "less decorous methods of dealing scientifically

with a rough antagonist, by enclosing and disarming in case of a sudden

encounter". To be

fair, Castle did update and revise his Schools and Masters

of Fence several times and indications were that he would have

continued doing so under Hutton's influence. Given a subject as broad as a history

of fencing, it is by all means excusable to have errors, especially

in a work as large as Castle's. As a major secondary source, his text is among the most useful

references for this subject. Studying at length its almost 300

pages is like taking a university course in the history of Renaissance

martial arts. Castle also published articles such as, "Some Historic

Duels", in 1894 and, "The Sword Duel, its history and its

practice", in 1895.

In considering Castle's contribution, (or that of any writer of

fencing history for that matter) we might

recall the words of an earlier British writer on the subject, Joseph Roland, fencing

master of the Royal military Academy at Woolwich, Greenwich, who in his 1809, Amateur

of Fencing, shrewdly noted: "That there are persons of mistaken ideas in almost

every Art or Science, is what few will deny. Yet I am inclined to believe there are more

erroneous opinions entertained with regard to the Art of using the Sword than on

most other subjects."

|

An 1893

demonstration in Britain ...very

likely by Hutton's own group

|

Perhaps it may have been the lack of a surviving

indigenous British fencing "tradition" which encouraged

the exploration of Medieval and Renaissance methods by these gentlemen.

In a sense this left them free to pursue all European fencing legacies,

Italian, French, German, Spanish, etc. However, the growing interest in Medieval

and Renaissance arms at this time was no doubt fueled by English antiquarian

Samuel R. Meyrick who in 1824 published the successful three-volume,

A Critical Inquiry into Ancient

Armour, while in 1845 John Hewitt produced his, Ancient Armour & Weapons. Each was a significant contribution

to the study of historical arms and helped channel a

growing interest in chivalric culture. In 1839 English nobles had

even organised a tournament re-enactment at Eglinton complete with

attempts at jousting in antique and replica armor.

Swedish arms historian William Reid speculated: "Perhaps

it was a reaction against the massive social changes brought about

by the Industrial Revolution that made the distant past take on a

new romance in the late eighteenth century. Throughout Europe, but

perhaps in Britain more than anywhere else, men were tending to look

back to the seemingly marvelous chivalry of the Middle Ages and of

the early Renaissance."

This is in no way to diminish the important historical fencing

research done by other great practitioner/researchers of the age such as Auguste Demmin,

Emil Merignac, Gustav Hergsell, Karl Wassmandorf, Jacopo Gelli, Gabriel

Letainturier-Fadin, A. Weyersberg, W. Boeheim, E. De Leguina, and Francesco Novati. However, unlike these researchers and writers, the

British were actively forming clubs to practice and study the old skills and bring them to

the public's attention. In the 1890s, the French AcadŽmie de Escrime (revived

in 1886) was also doing similar experiments in resurrecting what had been done with

antique weapons, but more as a curiosity than a matter of a surviving tradition or attempt

to reconstruct Renaissance martial arts. As well, the Germans at the beginning of the 20th

century were as fanatic about early arms and armor as the British, perhaps more so given

their unique heritage. They wrote

voluminously on Medieval and Renaissance weaponry and fencing up until the 1930s. Sadly,

much was lost in post war years and what little remains has gone largely unappreciated. Interestingly

enough, Carl Thimm

recounted an 1891 display at the Empire Theater of Varieties in London by "Professor

Hartl's Corps of Viennese fencing ladies" who conducted "masterful"

fencing displays including "rapier and dagger duels" wearing masks and padded

cuirasses of leather. A rare photo from c.1888 recently discovered of "Hartl's

ladies" actually shows them posing on stage with modern foils and flexible daggers.

A rare photo of Burton

A rare photo of Burton

late in his life (taken from his biography)

|

Another important figure from

this period must be mentioned. Though his death in 1890

at the age of 70 prevented his active participation in the

revival of historical fencing spawned by Hutton and Castle,

Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton is unique in the annals

of fencing historians. Burton was the first to call

the history of the sword the "history of humanity."

A soldier and erudite scholar, Sir Richard was at various

times a swordsman, duelist, secret agent, explorer, adventurer,

translator, world traveler, ambassador, and historian.

Of Burton, the arms curator Forbes Seiveking wrote in 1910,

he "was throughout his life an ardent student of the theory,

and an acknowledged master of the practice, of the art of

swordsmanship". A fencer who had personally engaged in combat,

Burton was also the first to discover, translate, and bring

to the West both the Kama Sutra and the Arabian

Nights, and was the first non-Muslim to visit the holy

city of Mecca (disguised as a Muslim at that).

He

traveled throughout the Middle East, India, and Afghanistan,

trekked crossed Africa and eventually became ambassador

to Brazil. Burton was a lifelong writer and studied fencing

at Boulogne, where he became a maître d'armes in 1853 at

the age of only 31. He had first started fencing at the

age of twelve. Colonel Arthur Shuldham described seeing

Burton fence in 1851 against a skilled sergeant of the French

Hussar in Boulogne. He wrote how Burton wearing only a mask

and shirtsleeves faced his adversary who wore a leather

jacket and head guard. To the astonishment of the

gathered crowd, seven times in a row he disarmed his man

on the first blow. With the exception of a single

poke in the neck Burton was unscathed. He

traveled throughout the Middle East, India, and Afghanistan,

trekked crossed Africa and eventually became ambassador

to Brazil. Burton was a lifelong writer and studied fencing

at Boulogne, where he became a maître d'armes in 1853 at

the age of only 31. He had first started fencing at the

age of twelve. Colonel Arthur Shuldham described seeing

Burton fence in 1851 against a skilled sergeant of the French

Hussar in Boulogne. He wrote how Burton wearing only a mask

and shirtsleeves faced his adversary who wore a leather

jacket and head guard. To the astonishment of the

gathered crowd, seven times in a row he disarmed his man

on the first blow. With the exception of a single

poke in the neck Burton was unscathed.

|

As

Hutton later did, Burton also wrote on the military use of

the bayonet. His Sentiment of the Sword, published

in 1911 but written decades earlier, is an intriguing look

into a time when fencing was changing from art of self-defense

to martial sport. Burton's famous

work was his 1884, The Book of the Sword. While occasionally

mistaken in information and now somewhat outdated, it is a

splendid read and a fascinating reference. His self-accumulated

knowledge of ancient swords in particular was considerable. As

Hutton later did, Burton also wrote on the military use of

the bayonet. His Sentiment of the Sword, published

in 1911 but written decades earlier, is an intriguing look

into a time when fencing was changing from art of self-defense

to martial sport. Burton's famous

work was his 1884, The Book of the Sword. While occasionally

mistaken in information and now somewhat outdated, it is a

splendid read and a fascinating reference. His self-accumulated

knowledge of ancient swords in particular was considerable.

The introduction to his work

contains some of the most eloquent testaments to the cultural

and historical importance of the sword yet written. He had

planned two follow-on volumes, with part II covering Medieval

and Renaissance swords. But, as the first book oddly was a

commercial failure, the others were never finished. Tragically,

his widow later burned all his notes. Burton's knowledge was

unrivaled in his day and his experience in the ethnographic

study of the sword was unparalleled. It would have been very

interesting if Burton has finished his planned second volume.

In 1898, Colonel Cyril Matthey, colleague

of Hutton and Castle, reintroduced the world to, The Works

of George Silver. Cyril G.

R. Matthey was Captain of the London Rifle Brigade, a member

of the London Fencing Club, and member d'honneur du cercle

d'escrime de Bruxelles. He also wrote the introduction

to Hutton's, The Sword and The Centuries. Matthey

was the first to present Silver's two Elizabethan

texts, Paradoxes of Defence and Bref Instructions

on My Paradoxes of Defence, in one volume.

|

A

painting of Burton in his fencing outfit A

painting of Burton in his fencing outfit

|

|

Hutton in his later years, from

Vanity Fair

|

Perhaps influenced by Silver and Hutton, or

perhaps just being a pragmatic old soldier, Matthey had much

to say about the lack of earnest martial intent in modern fencing

practice. Of the fencing in his

own time he declared, "I suggest that sword fighting is not

taught and that it ought to be. Fencing should be encouraged

to the utmost, but fighting should be regarded, as a distinct

subject, and of much greater importance in the majority of cases."

Profoundly,

Matthey further declared, "The fact that so little distinction

is now made between the swordsmanship of the duelist and that

of the soldier must be incomprehensible to the majority of fencers

who have given any consideration to the matter as thus defined.

Fencing as now taught throughout Europe is made, and always

has been, entirely subservient to 'the duel', with all its attendant

etiquette." Profoundly,

Matthey further declared, "The fact that so little distinction

is now made between the swordsmanship of the duelist and that

of the soldier must be incomprehensible to the majority of fencers

who have given any consideration to the matter as thus defined.

Fencing as now taught throughout Europe is made, and always

has been, entirely subservient to 'the duel', with all its attendant

etiquette."

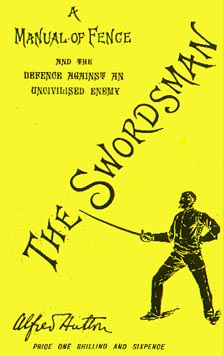

Captain Hutton declared it most accurately when,

in his 1898 text on sabre, bayonet, and arm seizes, The

Swordsman - A Manual of Fence and the Defense

Against an Uncivilised Enemy, he similarly stated,

"Those old masters taught fighting, we teach

nothing but fencing nowadays".

These sentiments are of course very nearly the

same of George Silver some 300 years earlier when he complained

the dueling style of the rapier did not prepare Englishmen for

the needs of the battlefield. Hutton's work ends

by stressing the need among British colonial soliders for realistic

fighting skills for facing an "uncivilised enemy."

|

Matthey felt

so strongly that fencing in his time, or at least the quality within

the British military which was formulated by continental teachers,

was no longer a martial art that he suggested: "Why not, having

decided upon the pattern of a regulation sword, have drawn up, or

have caused to be drawn up, by one of our well-known swordsmen...a

simple, common-sense method of swordfighting suitable for service requirements...That such a system

can be drawn up, and that there are those who are thoroughly qualified

to do it well, there is no doubt." Here he was perhaps referring to his

colleagues, Hutton and Castle. Matthey was not talking about

fencing for the increasingly vanishing private duel to "first

blood" with its associated frequent etiquette and urbane ritual,

but the battlefield encounters of British soldiers against what he

called "savage native contingents".

In

contrast to its continental neighbors of the 19th century,

it was the British Empire that was sending its armies all over the

globe to engage indigenous inhabitants –who, unlike most all

Europeans, were still fighting effectively with ancient traditional

swords, knives, spears, clubs, and bows. The British army's

experiences in East Africa, South Africa, India, Afghanistan, and

Asia taught them well the lessons of ill-preparing men for earnest

hand-to-hand fighting by using the "dueling school" approach.

…As the saying goes, if you don't use it you lose it. Hutton

said nearly this very thing in his earlier 1891 work, The Swordsman,

describing how with their swords and shields native Afridi

warriors would effectively engage British soldiers in assaults. In

contrast to its continental neighbors of the 19th century,

it was the British Empire that was sending its armies all over the

globe to engage indigenous inhabitants –who, unlike most all

Europeans, were still fighting effectively with ancient traditional

swords, knives, spears, clubs, and bows. The British army's

experiences in East Africa, South Africa, India, Afghanistan, and

Asia taught them well the lessons of ill-preparing men for earnest

hand-to-hand fighting by using the "dueling school" approach.

…As the saying goes, if you don't use it you lose it. Hutton

said nearly this very thing in his earlier 1891 work, The Swordsman,

describing how with their swords and shields native Afridi

warriors would effectively engage British soldiers in assaults.

At

the risk of being labeled "Anglo-centric", what is unique about these

19th century British soldier-scholar antiquarians, such as Hutton,

Castle, Thimm, Matthey, Pollock, and Burton, is that rather than an

academic game of the fencing salle or a skill of the

fading duel of honor, they viewed swordsmanship as practical knowledge

that was still a necessity for military men. Yet, rather than using

then current systems of fencing, they pursued the old forgotten styles

using the historical manuals as their guide. Though often dismissed

or criticized as mere "Victorian romantics", their influence was significant

in its day. It perhaps has had a greater

impact on historical fencing study today than ever before. At

the risk of being labeled "Anglo-centric", what is unique about these

19th century British soldier-scholar antiquarians, such as Hutton,

Castle, Thimm, Matthey, Pollock, and Burton, is that rather than an

academic game of the fencing salle or a skill of the

fading duel of honor, they viewed swordsmanship as practical knowledge

that was still a necessity for military men. Yet, rather than using

then current systems of fencing, they pursued the old forgotten styles

using the historical manuals as their guide. Though often dismissed

or criticized as mere "Victorian romantics", their influence was significant

in its day. It perhaps has had a greater

impact on historical fencing study today than ever before.

The

discoveries and advances in this subject made by men like Hutton,

Castle, and their comrades evidently did not survive past WWI.

The generation of youth whom they taught and inspired perished

in the horror of the trenches. It was not really until the 1990s that

the approach to historical fencing studies they promoted was attempted

again. The ARMA itself was to a large part created as a way of following

the effort these men first began. John Waller, head of fight interpretation

at the Royal Armouries in

Leeds, has expressed how the efforts of Hutton and Castle were a direct

influence upon the museum's conception of historical fencing demonstration.

In many ways, today's enthusiasts of Historical European Martial

Arts attempting to construct a modern curriculum are the inheritors

of the efforts by these "private gentleman devoted

to the noble science". It can only

be hoped that in a hundred years, some of us today are remembered

as fondly for our contributions. The

discoveries and advances in this subject made by men like Hutton,

Castle, and their comrades evidently did not survive past WWI.

The generation of youth whom they taught and inspired perished

in the horror of the trenches. It was not really until the 1990s that

the approach to historical fencing studies they promoted was attempted

again. The ARMA itself was to a large part created as a way of following

the effort these men first began. John Waller, head of fight interpretation

at the Royal Armouries in

Leeds, has expressed how the efforts of Hutton and Castle were a direct

influence upon the museum's conception of historical fencing demonstration.

In many ways, today's enthusiasts of Historical European Martial

Arts attempting to construct a modern curriculum are the inheritors

of the efforts by these "private gentleman devoted

to the noble science". It can only

be hoped that in a hundred years, some of us today are remembered

as fondly for our contributions.

Today, the legacy of Castle and Hutton has been carried on in the

research of professor of Renaissance studies, Dr, Sydney Anglo, culminating

in his monumental book in 2000, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe,

has become profoundly important in the reemergence of this subject.

Dr. Anglo's body of work is to the field of historical fencing today

what Castle's was in the 1890s. It's unparalleled content has become

the Bible of study for any serious student of historical European

fighting arts. While at once celebratory and revisionist, the

sheer volume of detail and scope of material Anglo covered both surpasses

and pays homage to the efforts of earlier explorers. Viewed

in perspective then, in their attempt to recover historical fencing

methods, what Castle and Hutton et al were doing was without question

what we today now call practicing Renaissance martial arts.

In light of his efforts into both academic scholarship and physical

reconstruction of the art, as well as educating the public and teaching

youths, Castle himself was the pioneer—an inspiration as the

first "professor of historical fencing studies." If anyone were

to be declared "the father of Western martial arts" it would indisputably

be Egerton Castle. Though, given the company he kept, I imagine he

himself would never presume such a title.

Egerton Castle

"Father of Historical Fencing Studies"

- from a Vanity Fair profile, age 42

Note: the preceding was excerpted from a forthcoming book on the modern

practice of Renaissance martial arts. All reference footnotes have been removed from this

online version. All images (excluding Burton's photo) are from original copies in the

author's collection.

©

Copyright 2001 by John Clements All rights Reserved. No part of this

may be reproduced without the explicit permission of the author. Revised march 2011.

|