An

Interview

with

Noted Sword and Weapons Expert

Hank Reinhardt

Note: The following content does not reflect official

views or opinions of either ARMA or its members.

Part I - May '99

Hank Reinhardt's contributions to the study of historical European

weaponry and fighting arts are not widely known outside of diehard enthusiasts. Although

he has practiced for over 45 years, until recently headed Museum Replicas Limited in

Conyers, Georgia, is recognized as an expert in handgun and knife fighting, was virtually

undefeated for seven years in the SCA, and founded HACA, he has actually written very

little and only privately taught a handful of select students.

Hank admits to being a frank SOB who has no patience for the BS that

surrounds the subject of his life-long passion. At a spry and active 66 his

unequalled knowledge and hands-on skill with Medieval and Renaissance weaponry has become

legend in some circles (See his Profile under the

Spotlight section). ARMA presents the first of a series of exclusive candid

interviews with this living resource.

ARMA:

You've been interviewed several times before for various magazines and newspapers, but

never before by an associate specifically for an audience of fellow practitioners.

Therefore, let's just start off in a general direction and let it flow from there . . .

What would you say is the single most misunderstood aspect of Medieval swords today?

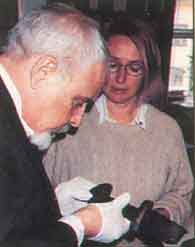

| Hank Reinhardt examines a Viking sword

during a recent research trip. |

|

|

Hank Reinhardt:

I'd say there were two, the weight and how they are used …this "edge to

edge" nonsense. The belief that Medieval swords were heavy, [which is] promoted in

all [these] books and magazines by people who never picked up a real [antique] sword. It's

really irritating too, because in talking with Ewart [Oakeshott], he was pointing out they

know better but still put it in there [many common references]. One [authority] on

the Crusades stated they were "too heavy for modern man to handle". I know

modern man can be weak but what? He can't pick up three pounds? That really

grates on me. Guys call me up at the company (MRL) and say "I'm strong, I'd like a

heavy sword". I don't care how strong you are, it doesn't matter, a heavy blade

is just more mass to do what a lighter blade would do as just well. They don't

understand. |

The other thing is…again, I've gone over this many times…what

happens to the edge of your sword blade when struck.

ARMA:

You mean it gets quickly chewed up.

HR:

Damaged. Exactly. Starting only about the 18th century military blades began to be

less sharp. It was thought -- or rather more correctly they realized -- you could do

about as much damage on an unarmored man with dull blades as with sharp ones, so they

stopped sharpening sabers as much. Sabers from that period generally have almost

flat edges. Parrying with the edge was less relevant and damage to the edge was a little

bit immaterial -- it lasted longer, too. A thin bar of steel, when you hit hard,

still did a helluva lot of damage when you hit someone.

ARMA:

And this still carries over today in

performance sword fights in movies and television, as well as what is taught in the sport

of modern saber fencing. This is all a result of the erosion of a life-and-death martial

art into a pastime.

HR:

Case in point is the British experience against -- oh, I think it was the north Indians --

where they were taking discarded British swords, sharpening them and then going and

[practically] cutting soldiers in half. The British were astonished, and when asked

how they managed this, [the Indians] said, "Oh we used your blades, they're very

good." This shocked [the British]. When they asked how [the Indians] taught

fighting, they said, "Oh, we don't teach anything, we just run up and hit really

hard!"

ARMA:

Yes, the British had lost the old

martial traditions of antagonistic fighting with blades, man to man in earnest. . . . What

would you say then is among the most admirable distinctive qualities of Medieval swords?

HR:

Well, what makes them so good is they are designed to kill people! [laugh]. Seriously

there was great experimentation in Europe among sword designs -- it was a very dynamic

society. Their sheer inventiveness I find most interesting. We sit around trying to figure

out what is the "perfect sword," and although I don't criticize the intent, we

can't do it.

ARMA:

Each type has its own utility?

HR:

Well, it's very much like a gun, it depends on what you want to do with it -- you can't do

everything, there's always trade off. A good smith, in trying to produce a weapon with a

good hard edge but tough and resilient, had to do this with almost a total lack of

technical knowledge -- they didn't know what made iron into steel. They thought steel was

a pure form of iron rather than just the reverse.

Take the rapier: Certainly a well-made rapier is a superb weapon for individual combat

against most single swords one-on-one, but add in other items of offense or defense and it

changes things drastically. Let me give you an illustration that comes to

mind. I was playing with a friend of mine several years ago and as you know I'm an

addict on kukris [the concave Nepalese fighting knife]. I had one out there -- so he

armed himself with a rapier, I took the kukri and we went at it. Well, we had about

seven or eight fights which I won all. I closed inside the rapier and whacked him

with the kukri. Well, he wanted to swap blades so he could try it, and we did and he lost

all the fights with the rapier because I used it in a completely different method than

what he used it for. He used it to "kill" me -- to get a good solid thrust

in. I used it like a sewing machine -- I didn't care how deep I go or where I hit

him, I wanted to hit him as many times and as rapidly as possible in as all sorts of

areas.

ARMA:

Right, right, very nice.

HR:

If I extend the blade I allow him to close with me. I do not allow him to close with

me. I did the same with Charles [Daniels], a superb ninjutsu practitioner, not like

this movie nonsense. He did the same at the Atlanta fencing club and nobody could

touch him, but he wouldn't do it with me simply because I wouldn't attack him like they

did.

ARMA:

You fight rather than

"fence"?

HR:

More or less.

ARMA:

What advice would you give

students/practitioners today to go about realistically training and learning with

historical European weaponry?

HR:

First thing I would do is learn the weapon, and by that I mean get the [reference] books,

read them. I still think The Archeology of Weapons [by Ewart

Oakeshott] is the single best written in the field.

Learn to evaluate what each sword is good for what each weapon is good for. What one

has to do is learn to evaluate the weapon's potential and the circumstances you are using

it in. This is something that should be done automatically…I really don't know

if it's something you develop or are born with.

[Also] when you are dealing with a life and death situation, deception is one of the

most important things in swordplay, you always make [the opponent] think you're going

someplace you're not.

ARMA:

Would you say it's about understanding

the inherent offensive and defensive strengths of how the weapon is handled and then also

understanding the underlying principles of fighting themselves?

HR:

And then be able to evaluate the situation you're in.

Continue to Part

II