|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

An edition of Jörg Wilhalm’s Fechtbuch from c.1540 includes a dozen pairs of sword and buckler figures showing actions very similar to those of the MS I.33 almost 250 years earlier. Even bastard swords with bucklers appear in 10 pairs of figures from an anonymous German manuscript of c. 1500 (Lib. Pic. A. 83, Staadsbibliothek, Berlin) which displays techniques such as punching, kicking, tripping, blade grabbing, and disarming.

Interestingly,

while many German fencing manuals of the 1400s include some material

on sword and buckler the two major Italian works known from the period

do not. The Master Fiore dei Liberi in his systematic work,

the Flos Duellatorum, of 1410, for instance, included longsword,

dagger, spear, polaxe, and wrestling but nothing on fighting with

or against the sword and buckler, or any shields. As well, while

the sword and buckler tradition later appears in Italian, Spanish,

and English fencing manuals from the 1500s, it oddly disappears from

major German fencing works by the mid 1500s. For example, it

is entirely absent from Paulus Hector Mair’s immense tome of

c.1540 that includes a wide range of weapons from dagger to sickle

to long staff. It is also absent from the various works of Joachim

Meyer from 1560 and 1570 and does not appear in later German fencing

manuscripts of the decades following.

Interestingly,

while many German fencing manuals of the 1400s include some material

on sword and buckler the two major Italian works known from the period

do not. The Master Fiore dei Liberi in his systematic work,

the Flos Duellatorum, of 1410, for instance, included longsword,

dagger, spear, polaxe, and wrestling but nothing on fighting with

or against the sword and buckler, or any shields. As well, while

the sword and buckler tradition later appears in Italian, Spanish,

and English fencing manuals from the 1500s, it oddly disappears from

major German fencing works by the mid 1500s. For example, it

is entirely absent from Paulus Hector Mair’s immense tome of

c.1540 that includes a wide range of weapons from dagger to sickle

to long staff. It is also absent from the various works of Joachim

Meyer from 1560 and 1570 and does not appear in later German fencing

manuscripts of the decades following.

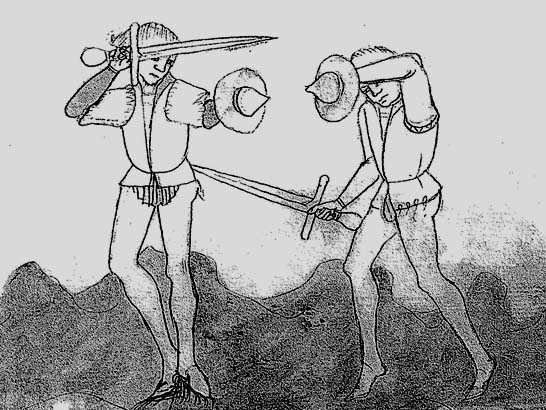

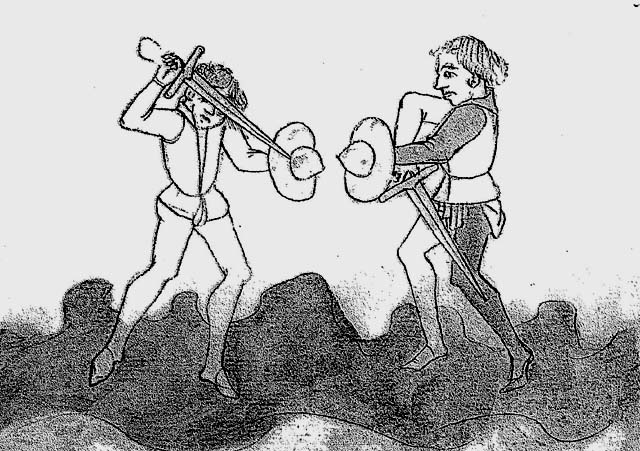

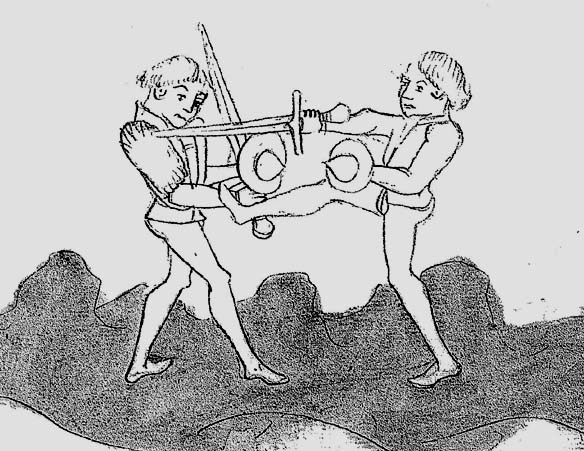

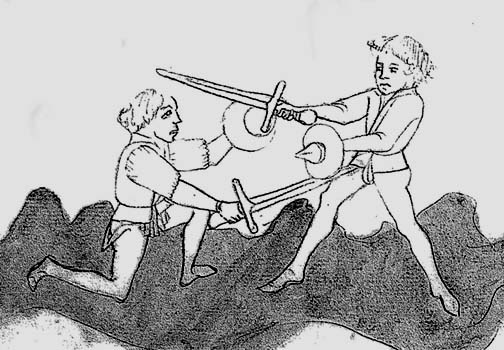

Images

from one anonymous late 15th century German fighting

text depict

the basic guards along with a range of actions. including fighting

against a spear, kicking, and dropping to one knee on a thrust.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1631, John Stow stated that around the year 1560 the “ancient English fight of sword and buckler was only had in use”, implying in a sense that the sword and buckler was seemingly indigenous to the British Isles, which in fact it was not. Stow’s real meaning was that the “foyning” fence of the new rapier had yet to be introduced by 1560. While the sword and buckler was by no means exclusive to England in the 1500s, the master George Silver is perhaps the best-known advocate of the sword and buckler. In his now famous 1599, Paradoxes of Defense, Silver actually complained that no thrusts were then being used in buckler play and that bucklers at the time were themselves not even being used in the fencing schools. This is somewhat odd, since students of English fencing guilds at the time are recorded as having played for their Prizes with sword and buckler. In 1615 the anonymous author of Third University of England (possibly Sir George Buc) also described how: “In the city there be manie professors of the science of defence, and very skillful men in teaching the best and most offensive and defensive use of verie many weapons as…[including] the sword and buckler…and others.” (McDermott, p 100). Yet, in support of Silver’s comment, Sir Thomas Middelton’s play of 1600, The Blind Beggar, did include the interesting comment “the common fight of these same serving men is sword and dagger, therefore I’ll choose the sword and buckler, they are unskill’d in’t.” (Craig, p. 10, note 28). Of the sword and buckler, George Silver admitted, “I confess, in old times, when blows were only used with short Swords & Bucklers, & back Swords, these kinds of fights were good & most manly, now a days the fight is altered.” (Paradoxes, Chapter 10). By this he meant that the newer foyning fence of the rapier was the cause of the change.

Silver

believed the weapon combination was one of the most effective.

In the opening to Chapter 21 he declared, “The sword and buckler

has the advantage against the sword and target, the sword and dagger,

or the rapier and poniard.” Yet, he also felt the sword and buckler

less effective for warfare than the sword and shield. Describing the

dynamic of battlefield arms in his day, Silver noted: “Yet understand,

that in battles, and where variety of weapons are, among multitudes

of men and horses, the sword and target, the two handed sword, battle

axe, the black bill, and halberd, are better weapons, and more dangerous

in their offence and forces, than is the sword and buckler, short

staff, long staff, or forest bill. The sword and target leads

upon shot, and in troops defends thrusts and blows given by battle

axe, halberds, black bill, or two handed swords, far better than can

the sword and buckler.” (Paradoxes, Chapter 21).

In Chapter 24 however, he stated, “the buckler, by reason of

his circumference and weight, being well carried, defends safely in

all times and places, whether it be at the point, half sword, the

head body, and face, from all manner of blows and thrusts whatsoever.”

And in Chapter 25, added, “The sword & buckler man out of

his variable, open & guardant fight can come bravely off &

on, false & double, strike & thrust home, & make a true

cross upon ever occasion at his pleasure.” As well,

in his unpublished work of c.1605, Brief Instructions, he noted,

“Of the sword & buckler fight” (Chapter 9) that “Sword

& Buckler fight, & sword & dagger fight are all one”

and it “is the surest fight of all short weapons.”

Silver

believed the weapon combination was one of the most effective.

In the opening to Chapter 21 he declared, “The sword and buckler

has the advantage against the sword and target, the sword and dagger,

or the rapier and poniard.” Yet, he also felt the sword and buckler

less effective for warfare than the sword and shield. Describing the

dynamic of battlefield arms in his day, Silver noted: “Yet understand,

that in battles, and where variety of weapons are, among multitudes

of men and horses, the sword and target, the two handed sword, battle

axe, the black bill, and halberd, are better weapons, and more dangerous

in their offence and forces, than is the sword and buckler, short

staff, long staff, or forest bill. The sword and target leads

upon shot, and in troops defends thrusts and blows given by battle

axe, halberds, black bill, or two handed swords, far better than can

the sword and buckler.” (Paradoxes, Chapter 21).

In Chapter 24 however, he stated, “the buckler, by reason of

his circumference and weight, being well carried, defends safely in

all times and places, whether it be at the point, half sword, the

head body, and face, from all manner of blows and thrusts whatsoever.”

And in Chapter 25, added, “The sword & buckler man out of

his variable, open & guardant fight can come bravely off &

on, false & double, strike & thrust home, & make a true

cross upon ever occasion at his pleasure.” As well,

in his unpublished work of c.1605, Brief Instructions, he noted,

“Of the sword & buckler fight” (Chapter 9) that “Sword

& Buckler fight, & sword & dagger fight are all one”

and it “is the surest fight of all short weapons.”

A

generation after George Silver, his fellow Englishman, Joseph Swetnam,

in his 1617, Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence,

took a very different view, declaring, “this I can say and by

good experience I speake it, that he which hath a rapier and a close

hilted dagger, and skill withall to use him hath great ods against

the sword and dagger, or sword and buckler.” On fighting

rapier against sword and buckler, Swetnam described the advantage

of its deceptive speed and reach in such an encounter:

A

generation after George Silver, his fellow Englishman, Joseph Swetnam,

in his 1617, Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence,

took a very different view, declaring, “this I can say and by

good experience I speake it, that he which hath a rapier and a close

hilted dagger, and skill withall to use him hath great ods against

the sword and dagger, or sword and buckler.” On fighting

rapier against sword and buckler, Swetnam described the advantage

of its deceptive speed and reach in such an encounter:

“By false play a Rapier and Dagger may encounter against a Sword and Buckler, so that Rapier man be provident and carefull of making of his assault, that hee thrust not his Rapier into the others Buckler: but the false play to deceive the Buckler, is by offering a fained thrust at the face of him that hath the Buckler, and then presently put it home to his knee or thigh, as you see occasion; for he will put up his Buckler to save his face, but can not put him downe againe before you have hit him, as aforesaid. Likewise you may proffer or faine a thrust to the knee of the Buckler man, and put it home to his buckler shoulder, or face, for if hee let fall his Buckler to save below, hee can not put him up time enough to defend the upper parts of his body with his Buckler.” (Swetnam, p. 83, 90, 95, 99 & 102).

Naturally, not all Renaissance fencing teachers were concerned with the sword and buckler method. Some may have felt they were not relevant to a gentleman’s needs in urban self-defense and private affairs of honor where the innovative rapier quickly gained predominance. It is no wonder then that the opening to the anonymous 1639 English manual on sword and rapier, Pallas Armata – The Gentleman’s Armorie, stated “that the Dagger, Gauntlet, and Buckler are not in use” (p. A2).

|

The preceding material was excerpted a forthcoming book on Historical Fencing due in 2003. © Copyright 2002 by John Clements.

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||